Sundance Review: Rita Moreno: Just a Girl Who Decided To Go For It

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

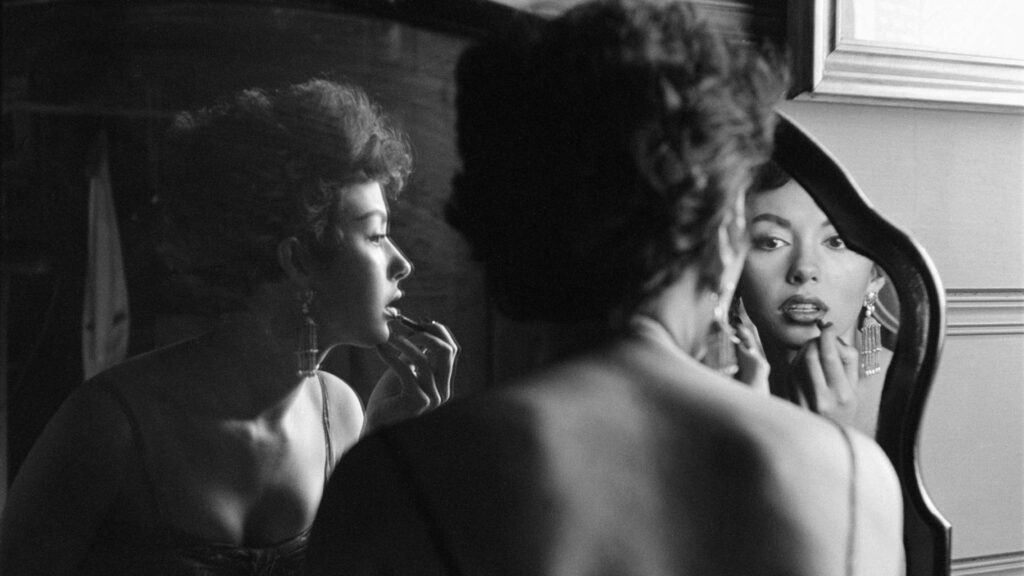

Rita Moreno is one of the greatest actresses of all time. The truth so evident in the modern era remained tragically elusive to many of the men who governed Hollywood for much of the early chapters of her illustrious career. The new documentary Rita Moreno: Just a Girl Who Decided To Go For It exposes these injustices, perfectly capturing the essence of the star whose mere stage presence is enough to evoke a smile on one’s face.

Director Mariem Pérez Riera sets an ambitious agenda for her documentary, covering a career that spans across seven decades. The audience hardly needs any reminders for why Moreno is so beloved, but the first few minutes perfectly set the tone for the film’s intentions. Moreno makes for a fascinating subject, willing to take the questions to depths that plenty would rather avoid.

Using extensive archival footage from Moreno’s early years on screen, Riera does a superb job illustrating the ways that nonwhite actors, particularly women, were boxed into offensive supporting roles. Moreno was forced to act in roles that required extensive tanning makeup and an accent to fit whatever race she was cast to play, a stark contrast from her normal voice. Hollywood’s racist past is no secret to anyone, but the documentary frames the extent of the discrimination in terms that prevent anyone from painting the era with rosy excuses of ignorance of a bygone era. It was always wrong.

The film spends a great deal of time focused on Moreno’s personal life. She recounts past traumas with intimate detail, freely opening up about sexual assault, an attempted suicide, her years-long relationship with Marlon Brando, marital unhappiness, among other life hardships that many prefer to keep to themselves. It’s incredibly moving to watch a woman with so much life experience reflect with such a raw degree of honesty.

Riera includes extensive interviews from Hollywood actors such as Morgan Freeman, Eva Longoria, and Lin-Manuel Miranda, who help provide some context as to the scope of her legacy. Moreno’s impact breaking down barriers for the Hispanic community cannot be understated, nor can her importance to American film as a whole. West Side Story is a great cinematic treasure, one that Moreno helped elevate beyond some its problematic aspects, something she continues to shape as part of Steven Spielberg’s upcoming adaptation.

Perhaps the greatest inspiration that Moreno provides is through her sheer determination. Never content with success, she remains a tireless advocate fighting for women’s rights, especially abortion access. To be a working actor in Moreno’s early years meant accepting some roles beneath her stature, but she never forgot her worth. There’s a lot of food thought in the documentary for working artists, especially in today’s climate.

Riera’s film dazzles both as a tribute to Moreno’s trailblazing career and a contemplative piece exploring life’s great inequities. This documentary is nourishing for the soul. Ninety minutes of Rita Moreno doing just about anything would make for a good film, truly one of popular culture’s most charming figures, but Riera puts together a marvelous narrative that beautifully captures the legacy of an icon.