Bully. Coward. Victim: The Story of Roy Cohn is an esoteric look at an American monster

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

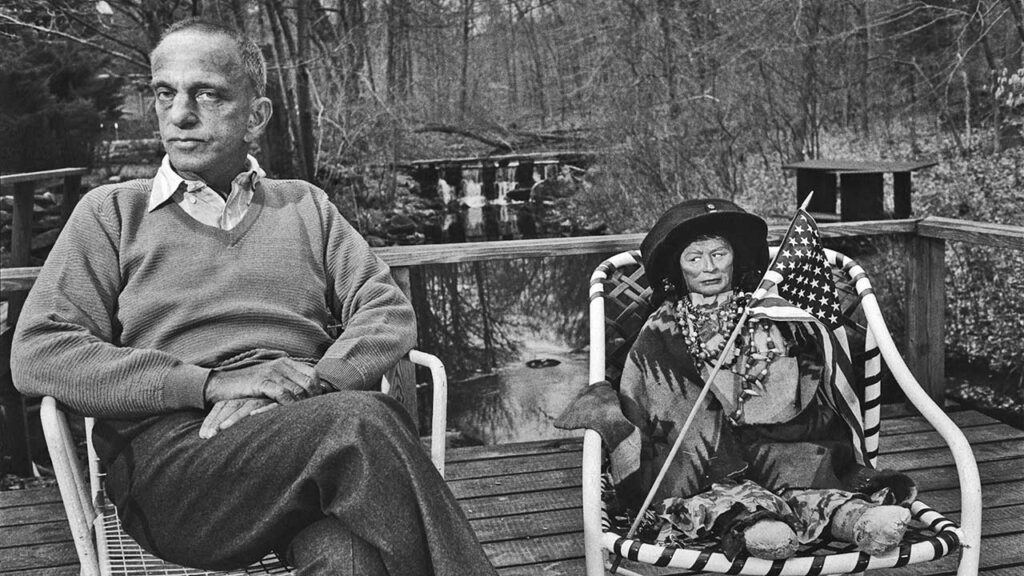

The stain of Roy Cohn may never be fully removed from America. A man who championed Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare and shepherded Donald Trump through his early days in business, it can be hard to understate his impact on this country. The new documentary Bully. Coward. Victim: The Story of Roy Cohn sheds some light on Cohn’s troubled existence.

Instead of aiming for an overview of Cohn’s life, director Ivy Meeropol focuses her attention on a few aspects of his career and personal interactions. The prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Meeropol’s grandparents, weighs heavy on the narrative. Meeropol’s father Michael is interviewed in the film, providing an intimate perspective to the specific human cost of Cohn’s carnage.

Meeropol also includes interviews with Cohn’s cousins, who hold nothing but disdain for their relative. The intimacy that these interviews suggest is not necessarily reflected in the documentary, but Meeropol’s angle is a valuable one, especially since there are plenty of works about Cohn’s life. It would, however, be easy to watch the film without realizing the relation between Meeropol and her grandparents.

Cohn’s homosexuality frames much of the narrative. Though closeted for his entire life, Cohn’s sexuality was not exactly much of a secret to those who knew him. Meeropol points out the ample hypocrisy present in Cohn’s endless bigotry toward homosexuals, a key figure in the Lavender Scare who repeatedly denied his own HIV diagnosis even in the last few weeks of his life.

The narrative is much more contemplative about Cohn’s life than biographical. Those who know little about Cohn might feel a little lost amidst Meeropol’s scattershot pacing. She’s a director with a singular focus to carve her own niche with regard to her subject. In that regard, she most certainly succeeds.

Trump doesn’t play a very large role in the documentary, though anyone familiar with his combative nature will see obvious parallels in Cohn’s speech patterns. Meeropol includes plenty of interviews that essentially let Cohn speak for himself. His own words are pretty damning, painting the picture of a detestable man.

The documentary hardly humanizes Cohn, with the “victim” in its title referring to a specific event rather than a general sentiment. There is some sympathy to be garnered in his tragic life, but Meeropol hardly endorse this idea. Cohn is repeatedly referred to as “evil” by subjects, though his true villainy hardly needs to be outlined. In that sense, Meeropol is perhaps a bit generous toward Cohn.

Bully. Coward. Victim: The Story of Roy Cohn is a compelling film, albeit one that hardly tries to be the definitive voice on Cohn’s life. Meeropol is a skilled storyteller with a keen sense of emotion. The documentary is a must watch for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of a truly loathsome figure in American history.