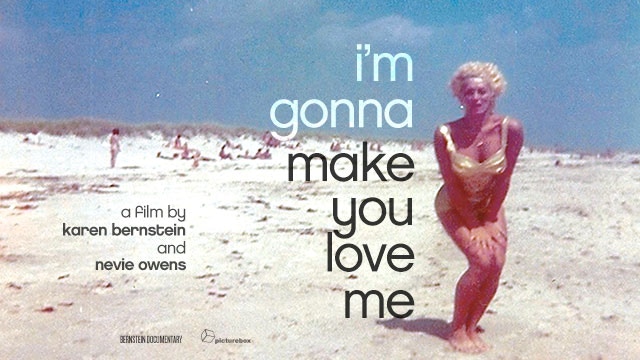

“i’m gonna make you love me” Is a Moving Portrait of a Life in Transition

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

Detransitioning, the process of transgender people returning to the sex one was assigned at birth, can be a touchy subject within the LGBTQ community. The notion of transitioning being a “mistake” naturally crosses most, if not all, trans people’s minds at some point in time, a natural feeling given the gravity of what’s at stake. The exact detransition rate can be hard to pinpoint due to differences in methodology used, but many peer reviewed sources have found the number to be anywhere from 0.3% to 3% among adults.

The documentary i’m gonna make you love me features a man named Brian Belovitch, who transitioned in the late 70s, living as Natalia/Tish for many years before reverting back. As Natalia, Brian got married, lived as an army wife in Germany, and performed in many nightclubs throughout New York City. The film presents a fascinating portrait of what life was like for trans people back then, as Natalia had seemingly little trouble living life as a woman, a stark contrast to the kind of narratives right-wing media pushes today.

Brian makes for a fascinating subject, an engaging man who wears his emotions on his sleeves. There are times when he clearly feels uncomfortable, but there aren’t any moments where it feels like he’s holding back. The archival footage contrasts well with his contemporary persona, a lively spirit who’s just trying to figure out who he is in this world.

Director Karen Bernstein features interviews from a number of people from various stages of Brian’s life, who help to add context to his transition. Brian’s family was far from supportive, even going as far as to blame him for adding stress to his mother’s life. Contemporary footage of Brian with his husband Jim helps take some of the edge off the often brutal narrative, giving the audience an assurance of a happy ending.

The documentary itself does have a bit of an identity crisis. As a film, i’m gonna make you love me largely aims to showcase the full picture of Brian’s life, past and present. The narrative is quite anchored to Brian’s transition and subsequent detransition. While Brian’s transition into Tish receives ample focus throughout the film, detransition is only covered for a brief portion toward the end.

Having thoroughly explored the origins of Tish, the film regrettably doesn’t have the same lust to dig deeper into the resurfacing of Brian. There are a few reasons offered to explain the detransition, including health and social considerations, but the brevity with which this is covered leaves a lot to be desired. To some extent, this is a natural product of the limitations of documentaries to adequately cover a full life within a ninety-minute narrative, but that’s also reflective of the choices that Bernstein made as a director.

There are people who will seek out this film as part of an effort to paint transitioning as a dangerous proposition with uncertain results. Brian has lived his life without regret. I’m gonna make you love me is not a film with an opinion of whether or not transitioning is a good idea, though many may try and twist Brian’s story to fit their own agenda. With that in mind, there’s an added importance to narratives like this one that showcase people rather than the ideas they’re supposed to represent.