Slamdance Review: Bad Attitude: The Art of Spain Rodriguez

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog

The counterculture movement of the 1960s produced some of the greatest comics ever crafted. Cities such as New York and San Francisco were home to countless underground magazines that put out work that forever changed the medium, moving comics away from children’s content toward more provocative messaging. The work of Manuel “Spain” Rodriguez stands out as among the most provocative and intellectually stimulating comics to come out of the underground movement.

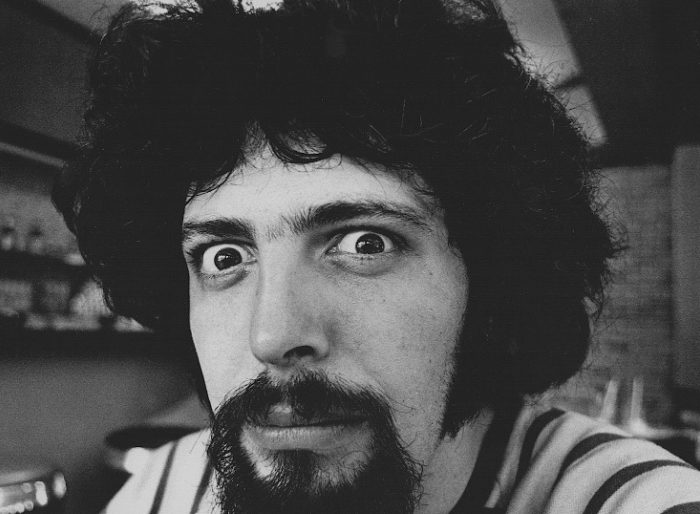

The documentary Bad Attitude: The Art of Spain Rodriguez follows the life and career of the late artist, who passed away in 2012. Featuring interviews with many of the leading artists of the underground movement including Art Spiegelman, R. Crumb, and Trina Robbins, the film does a great job explaining the era and its role in shaping comics as a medium. Spain’s work is constantly shown on screen, giving the audience a wonderful introduction into his immense talent.

Directed by Spain’s widow Susan Stern, the film often struggles with an unclear thesis. The first twenty minutes are spent providing a history of the countercultural movement, often intertwined with biographical details of Spain’s early life. The audience is given a pretty good idea of where to place Spain’s work within the broader context of the 60s, but that sense of clarity is sorely missing once the documentary starts to move away from that era.

As the title suggests, Spain as a person is a bit rough around the edges. Extensive archival footage doesn’t necessarily show a man with a bad attitude, but rather more of a chauvinistic figure. Much of Spain’s art is a bit sexist, occasionally homophobic, in nature to say the least. Stern’s footage of him paints a similar picture.

Spain’s casual misogyny is a subject that the film spends much of its seventy-one minute runtime dancing around while never really turning to face head on. Early on, an interview with a friend of Spain states that he never “punched down,” focusing his art instead on critiquing people in power. This idea is contradicted time and time again throughout the documentary, in Spain’s art, his own words, and even the testimony of other interviewees.

Worst of all, his artistic brilliance is undercut by the surface-level approach to his work. While often described by interviewees as a great progressive political thinker, the film only presents a surface-level understanding of Marx’s theory of labor value, the kind of pontificating you might expect from a couple of college freshmen smoking pot in their dorm room. One can forgive a film for not wanting to dive too deep into progressive ideology, but it hardly does a very good job elevating its subject in this regard.

Time and time again, Spain is presented as less of a countercultural figure than an edgelord looking to flip the bird at anyone and everyone. An early depiction of his time in a motorcycle gang depicts his clubhouse as flying a Nazi flag for no real reason other than to stoke controversy. His views on feminism paint him as more like a far-right cultural warrior than a progressive.

Plenty of testimonies from his family and friends suggest he didn’t believe a lot of this stuff, but for whatever reason, it’s still all presented in this rather short feature. Even at seventy-one minutes, the film feels way too long, a product of its uncertain direction. Worst of all, there’s not really a clear takeaway by the time the credits start to roll.

About halfway through the film, a narration from Stern poses a question about Spain’s complicated nature, wondering what this suggests about her for marrying him. The film signals its intentions to try and grapple with this concept, but it never really does. There are only so many times you can hear people say variations of “Spain said awful shit, but he was my friend,” before it starts to lose its impact.

Spain Rodriguez was a brilliant artist. Bad Attitude presents a murky picture of his life that’s bound to turn people off to his talents. Spain lived in a different era. One can look past his regressive sense of humor and misguided opinions, but after watching the film, it’s unclear who would want to. The film might have some value in its archival footage for fans of Spain, but it hardly makes a good case for why anyone else would want to dive into his work.