The Blech Effect squanders its runtime with a one-note premise

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

A film like The Blech Effect forces one to recognize the confines of the space that narratives occupy. Even documentaries that cover decades-long spans can only cover small snippets of a person’s life within a ninety-minute runtime. The impact of a documentary lies in its ability to capture the essence of its subject, not necessarily to paint a full portrait.

David Blech, once dubbed the “king of biotech,” could have been a billionaire, founding several companies within the field, including the makers of Cialis. Blech was involved with numerous controversies, eventually pleading guilty to two counts of criminal fraud, which earned him a lengthy prison sentence. Rather than be remembered as a man who helped cure cancer, Blech’s legacy is instead defined by his greed and criminal activity.

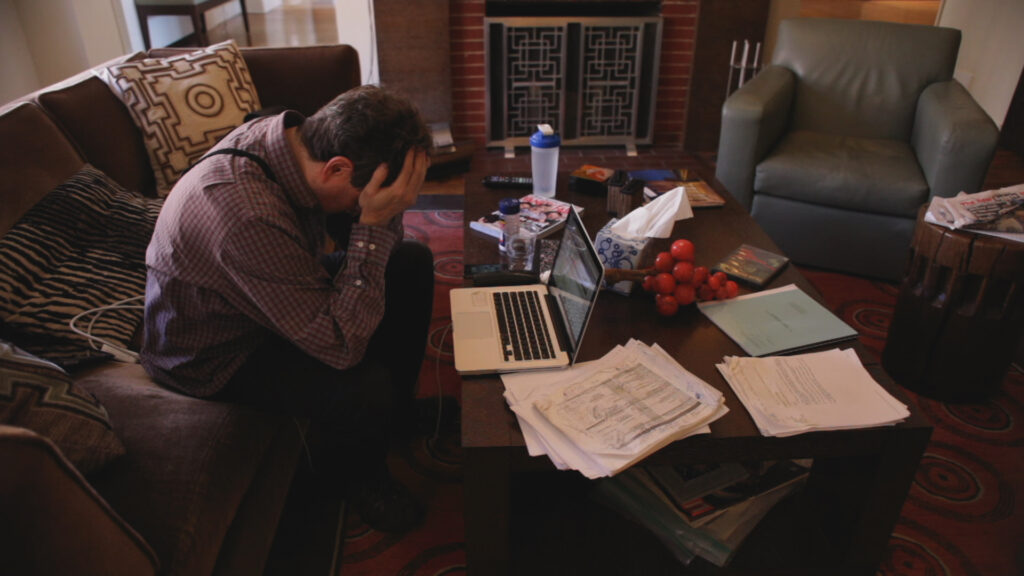

Director David Greenwald sets the film mostly in Blech’s large apartment in New York City, a luxurious space at odds with his dire financial situation. The narrative takes place before Blech served a thirty-month prison sentence. Understandably, Blech is very tense, worried about his family and the burden that his time in jail will have on his wife, left alone to care for their autistic son.

The film spends barely any time on Blech’s broader career. Greenwald is practically solely concerned with Blech being sad about having to go to jail. Blech’s gambling addiction receives a lot of attention, framing that helps paint him as fairly sympathetic. Trouble is, it’s not very interesting.

The Blech Effect spends its time throwing a lackluster pity party instead of offering any substantive insight into its subject’s career. There’s little time spent explaining biotech, leaving the impression that Blech is little more than a bad stock trader. Even the phrase “the Blech effect” isn’t really described all that well. Blech repeatedly talks about all the companies he started, never once stopping to consider how he might want to explain this shady-sounding business practice to a general audience. Anyone looking to learn more about David Blech as a person would be sorely disappointed.

What’s further puzzling is Greenwald’s efforts to garner sympathy for his subject. David is mildly likable, a father who clearly loves his son. So what? Greenwald lets Blech suggest that he’s only settling because he doesn’t have the resources to fight back without pushing back on this puzzling dynamic. The whole thing plays out like bad PR.

Greenwald essentially expects his audience to feel sympathy for a figure responsible for those annoying erectile dysfunction ads on cable television. Blech isn’t particularly remorseful, just sad. There is a fair degree of sympathy that one can extend to a figure who’s clearly an addict, but it’s hard to keep this up for an entire feature-length narrative.

To some extent, The Blech Effect might have value as a wake-up call for gambling addicts, but that idea is hampered by Blech’s singular status. David Blech has lost more money than most people will ever see in their lives. That premise could have made for an interesting documentary, but instead Greenwald spent his time panhandling for sympathy toward a disgraced, not all that remorseful, venture capitalist.