‘Ballerina’ review: excellent choreography proves there’s life left in the John Wick franchise

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

The John Wick franchise has relied on a fairly simple premise that has become quite convoluted with each passing entry. “All this over a dog,” has become short form for the ethos of the whole series. And for the most part, it’s worked, aided greatly by superb choreography and Keanu Reeves’ dedication to his craft.

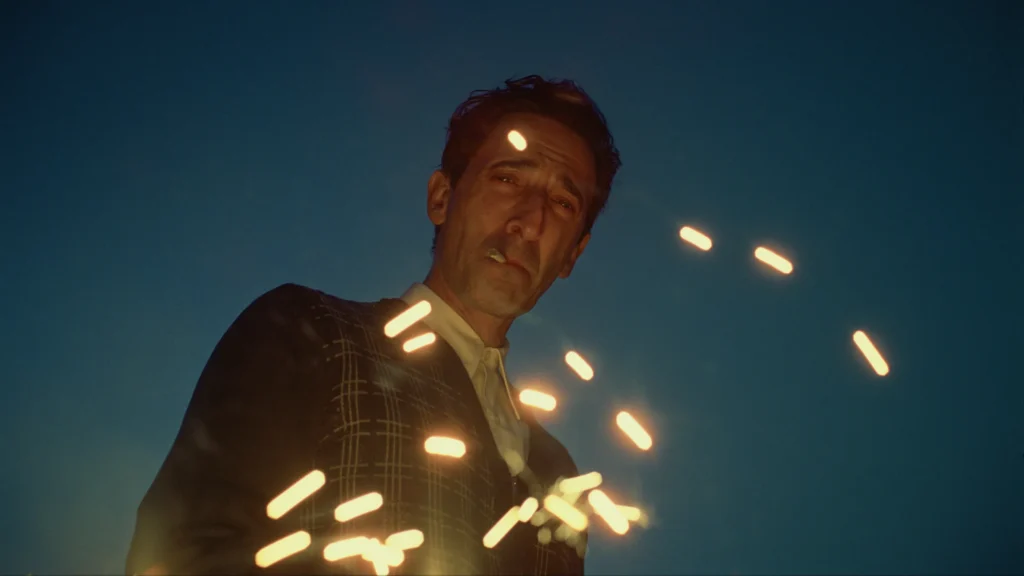

From the World of John Wick: Ballerina tests the series’ formula in a major way. What is John Wick without John Wick? Set during the events of John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum, the film tries to gently ease its audience into its world without its major hero at the helm.

The plot is quite perfunctory. Eva Macarro (Ana de Armas, replacing Unity Phelan, who portrayed the character in Parabellum) seeks revenge on The Chancellor (Gabriel Byrne), who killed her father, Javier (David Castañeda). Eva is a student at the Ruska Roma organization under the tutelage of the Director (Anjelica Huston). Eva goes rogue after the Chancellor, pitting titans of the High Table against each other.

De Armas brings a lot of charm to a largely empty role. Eva’s only substantive relationship in the movie is with the Director, limiting the effectiveness of Byrne as the villain. Franchise mainstays Winston Scott (Ian McShane) and Charon (Lance Reddick, making his final on-screen appearance since his 2023) provide limited mentorship in crowd-pleaser roles.

At times, the movie feels pieced together from various strands of plot. Norman Reedus makes a limited appearance that seems more destined for another spinoff. Catalina Sandino Moreno’s role as one of The Chancellor’s bodyguards contains more complexity than was needed for such a small role. Veteran director Len Wiseman seems more than aware that his film lacks much heart at the center, but he never really commits to a vision beyond the boilerplate revenge tale.

The film does deliver on the action. Not all of the sequences are up to John Wick standards, but there are a few genuine standouts amidst the lean 125-minute runtime. The film never shakes the sense that it could have produced a better product with a few more passes at the script, but aside from a few janky special effects sequences, Ballerina manages to deliver a satisfying experience for fans of the franchise. The action is fun. There are too many flamethrowers and grenades, but many of the stunts are a joy to behold on the big screen.

Keanu Reeves is also effectively deployed. This isn’t his movie, but John Wick gets a little bit more to do than just a standard cameo. The film manages to give him a few moments without leaving its audience desperate that he doesn’t play a bigger role.

Ballerina is not a great movie, which is a shame, because the pieces are certainly there. The story just isn’t strong enough to deliver an experience on par with the mainline franchise. The film is leaps above the terrible Peacock prequel, The Continental. It’s an enjoyable time at the theater. The franchise hasn’t completely figured out the formula to thrive without Reeves, but it’s a worthy start.