The Northman offers an arthouse spin on an epic legend of vengeance

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

Vengeance is an easy desire to rationalize. The injustice of suffering leaves a void that the heart naturally wants to fill. The cost of delivering such retribution often plays second fiddle to the mind’s manifestation of the sweet delight seemingly offered by correcting an egregious wrong. Of course, the world is not a binary of good vs. evil, not that vengeance has to care about such realities.

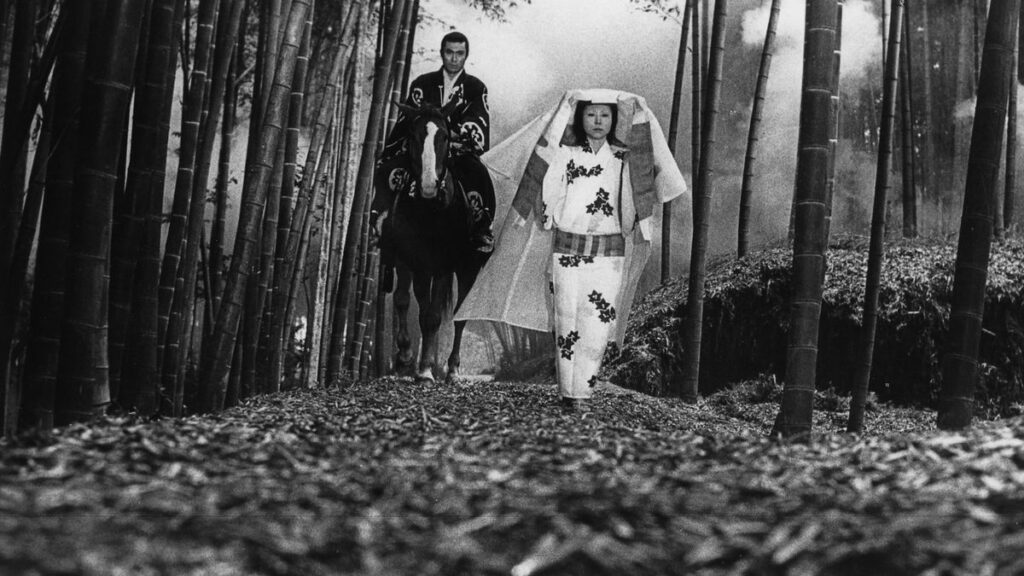

The Northman follows a life of vengeance. An adaptation of the legend of Amleth, a Scandinavian figure more familiar to Western audiences for inspiring Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the narrative follows the prince (Alexander Skarsgård, with Oscar Vovak playing Amleth as a young boy) as he seeks to avenge the death of his father King Aurvandill (Ethan Hawke) at the hands of his uncle Fjölnir (Claes Bang), who also burned his village and abducted his mother Queen Gudrún (Nicole Kidman). Prophecy shapes Amleth’s quest, believing himself to be put on the soil solely to take his uncle’s life.

Amleth gives up a promising career as a Viking berserker to stow away aboard a slave ship headed to Iceland, the seat of his uncle’s exile. Becoming enslaved himself in the process, he meets Olga (Anya Taylor-Joy), a sorceress and kindred spirit. As Amleth and Olga grow closer, the prince faces a fork in the road, the cost of his quest for vengeance contrasted by the prospects of breaking the cycle, to forge a new path free of the endless violence.

Director Robert Eggers delivers a slow-burn that’s singularly focused in its step-by-step depiction of Amleth’s submission to prophecy. Just as good and evil exist outside a binary, the question of nature vs. nurture is a bit irrelevant when faced with a reality where the two work in almost-complete tandem. Violence may not be the only life that Amleth could choose to live, but it is the only life he knows how to live. Eggers’ every motion hammers that point home.

The cast all seem to understand their place less as characters, but as part of the legend. Eggers seems to understand the weight of epic, the performances and cinematography carrying a soft touch even amidst the narrative’s extreme brutality. Skarsgård never once puffs his chest to assert his place as the hero, in complete alignment with Amleth’s sense of prophecy bestowed upon him at an early age. His approach to character development feels almost more like character actualization than any real sense of growth. Not all boys change as they grow into men.

The supporting cast, also including Willem Dafoe and Björk in bit roles, have quite a lot of fun with the material. The 137-minute runtime is a bit over-bloated, but Eggers never loses his grip on his audience through the cerebral narrative. Larger-than-life material is rarely delivered with such serene execution. Epics are not necessarily meant to feel intimate, yet The Northman carries itself like performers in a black box theatre, welcoming even against a backdrop of endless miles of nothingness.

The Northman demonstrates Eggers’ immense maturity as a filmmaker, a testament to cinema’s power to communicate rich art to a wide audience. In a world full of crowd-pleaser films fighting for their share of the box office, the film instead aims to leave its viewers with a calmer sense of satisfaction by the time the credits roll. It feels good to be challenged in the theatre, to see an epic wrestle with morals humanity has been grappling with for hundreds of years.