The Mandalorian Season 3 Review: Chapter 21

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Pop Culture, Star Wars, TV Reviews

The Mandalorian premiered at a precarious time for the Star Wars franchise. Hitting Disney+ just a month before The Rise of Skywalker landed with a thud in theatres, Mando and his adorable sidekick offered a palette cleanser to anyone depressed by the narrative abomination that was the sequel trilogy. One of the main draws of The Mandalorian was the distance it afforded viewers from the endless nostalgia sucking all the air out of the mainline franchise.

Season three is clearly intent on closing the gap between the series and the films a bit. The return of Dr. Pershing and his love of illicit cloning, along with the emphasis on Coruscant and its messy political landscape, point to an unpleasant reality that’s kind of hard to ignore. It seems very likely that Grogu’s DNA/midichlorians will be used as the foundation for whatever Snoke was.

Chapter 21, “The Pirate,” blends a few of the show’s plotlines together in a well-paced, action-heavy episode. The episode’s most important achievement was the validation of Nevarro as a position of narrative value rather than a convenient place to kill time whenever the show thought it might be fun to check in with Greef Karga. It is somewhat refreshing to see the show actually weave its older supporting bench into its long-term plans.

The return of Captain Gorian Shard was undercut by Nevarro’s inexplicable lack of defenses, Karga looking fairly inept at urban planning in the Outer Rim, a dynamic that’s harder to forgive when the episode leaned so heavily on his army-wrangling prowess in the early days of the show. The townsfolk were shown to have blasters at the end of the episode, but it’s more than a little lazy that none of them were shown to have lifted a finger when Shard first attacked. A meager attempt at a defense would have been understandable given the ship’s overwhelming firepower, but nobody even tried. How does Nevarro normally handle any sort of crime or violence?

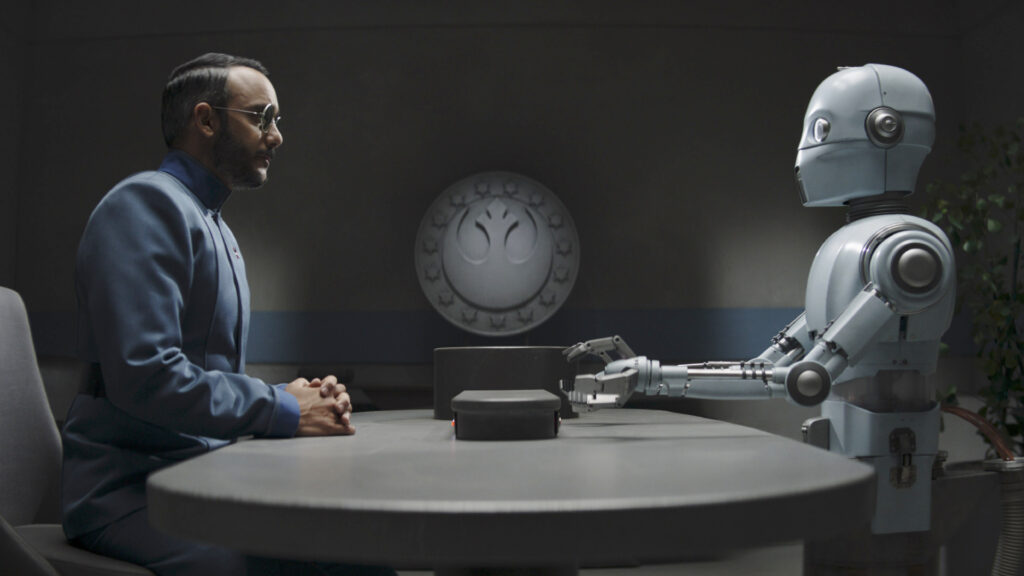

Having no one around to blast the giant spaceship that was later destroyed by a single N-1 starfighter, Karga turns to another recurring character, Captain Carson, to send the New Republic to help. Carson visits Coruscant in person for seemingly no other reason than to bring Elia Kane back into the fold after spending most of Chapter 19 following her adventures with Dr. Pershing. Colonel Tuttle’s apathy toward Nevarro effectively sets up some cracks in the New Republic, but it’s hard to call any of this particularly satisfying when Coruscant still feels so small despite having seemingly billions and billions of people living in the city.

The idea that R5-D4, used up until this point almost solely for comic relief, is some kind of rebel spy in active communication with Captain Carson is beyond absurd. Elements of the fandom have for decades leaned into the gag that R5-D4 is actually a hero of the Rebellion, deliberately sabotaging his own motivator in A New Hope so that R2-D2 could take his place. There’s even a canon story about R5-D4’s adventures, released as part of a charity book in 2017 celebrating the 40th anniversary of the franchise. It’s laughably silly to think that Pelli and her Tatooine junkyard are part of some grand conspiracy to drag the Mandalorians into helping remnants of the New Republic defend planets that didn’t sign the charter, but I guess the show wants to lean into this nonsense for whatever reason. Not everything needs to be connected!

The R5-D4 foolishness did serve a broader narrative purpose. The Mandalorians have looked a little aimless hanging out in their undeveloped rock fort. Defending Nevarro not only gave their tribe a chance to actually do something, building toward a future for their people instead of merely hanging on to relics of the past.

Chapter 21 contained multiple wins for religious zealotry. Paz Vizsla pulled an amusing bait-and-switch on Mando by pointing out the losses they’ve endured for his helmetless ward before urging the tribe to come to the aid of another man who tried to kill them all. The Armorer recognized the power of uniting their people regardless of who likes to feel some sunlight on their face every once in a while. Her sequence with Bo-Katan could have benefited from some additional build-up, something I mentioned last week, but it was still an effective way to move the Mandalore plot forward.

It’s also rather refreshing to see that the Armorer is taking Katan’s word on having seen the mythosaur, a rarity for a person in power to believe their own constituents. Between the mythosaur and the darksaber, Katan and Mando are clearly on a bit of a collision course, but for now it was rather touching to see the Mandalorians united, and accepted, on their new, likely temporary, home.

The action was very entertaining, if not a bit ridiculous. It’s hard to tell which group of pirates were more incompetent, the fools on the ground or the ones in the air, but the whole thing looked like a cross between Pirates of the Caribbean, Peter Pan, and Swamp Thing. For a blockbuster movie, that might be a bad thing, but the absurdity mostly worked as a mid-season episode of television.

The return of Moff Gideon has seemed inevitable since last season’s finale, sucking a little air out of the episode’s final scene, reminding us all of how light this season of The Baby Yoda Show has been on Baby Yoda. “The Pirate” demonstrated all the things that make The Mandalorian great alongside troubling concerns that the show is trying too hard to tie too much of Star Wars together. Distance from the sequel trilogy was one of the show’s biggest selling points. Some fans would prefer to pretend Snoke never existed, but it doesn’t look like we’re going to get that luxury. The Mandalorian is playing with fire at the risk of its own legacy, sacrificing its own self-contained beauty for a chance to redeem past failures.