Hurley Presents a Surface Level Narrative of a Fascinating Man

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

While the past decade has made great progress in removing the stigmas around homosexuality, documentaries like Hurley serve as excellent reminders for how difficult it can still be for some people to embrace being gay publicly. Professional sports, in particular, remains a fairly hostile environment for LGBTQ people, with many preferring to stay in the closet during their careers. The life of motorcar legend Hurley Haywood could have shed some light on this dynamic, but too often the film that bears his name is too reluctant to dive beneath the surface.

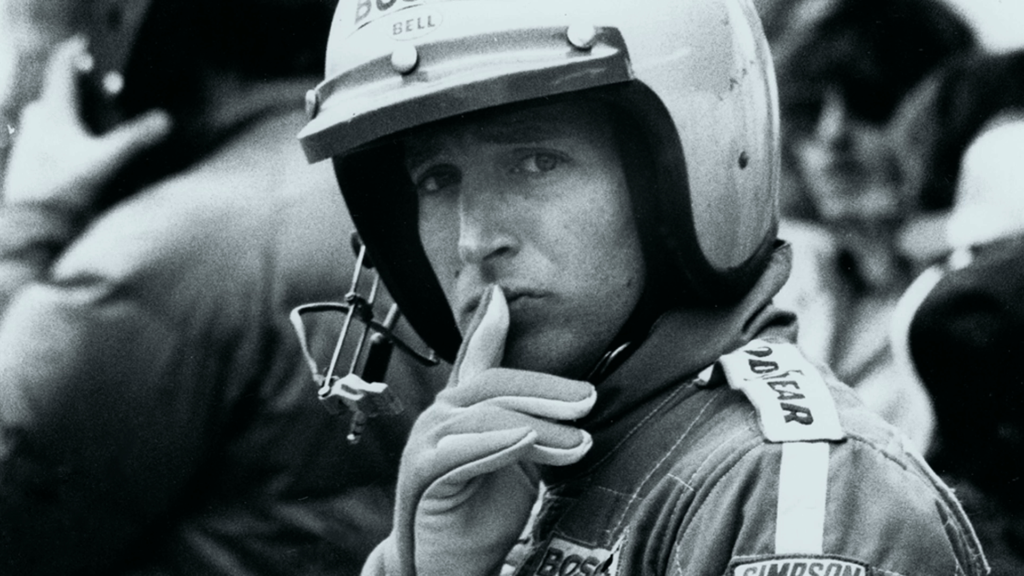

Hurley focuses on two separate narratives for most of its runtime, Haywood’s homosexuality as well as his relationship with teammate Peter Gregg, who committed suicide in 1980. Actor and racer Patrick Dempsey, who serves an executive producer on the film, offers context for Hurley’s place in motorcar lore. People unfamiliar with endurance racing might be confused at first, as the film doesn’t do much to explain the specifics, but you do get a sense for what sets Haywood apart from his contemporaries.

The documentary struggles with the contrast between Hurley’s racing achievements and his life as a closeted homosexual. Haywood has no trouble explaining his achievements throughout the film, at times coming across as rather boisterous, but he’s quite uncomfortable talking about life as a gay man in professional sports. The contrast in confidence is palpable, but the documentary is reluctant to pursue what it means for Haywood to have spent close to seventy years of his life hiding who he really was.

As important as Peter Gregg was to Haywood’s career as a racer, his prominence in the documentary seems puzzling at times. There are several instances where multiple interviewees criticize aspects of Gregg’s personality in sequence, though it’s unclear what larger purpose these accounts serve. The film isn’t ostensibly about Gregg, and its participants start to look a bit petty as they continue to harp on the deceased racer, a situation exacerbated by several interviews with one of Gregg’s children.

The film presents conflicting explanations for why Haywood chose to come out as this particular point in his life. Haywood himself offers up a touching account of a conversation he had with a young closeted gay man, clearly inspired by the profound effect he had on the individual’s life. This perspective is contrasted by Haywood’s clear reluctance to embrace the “activist” label. At one point, one of the interviewees goes on a long-winded diatribe about how Haywood should not become a gay activist, doing so with a kind of subtle homophobia that America continues to struggle with. The “tolerance but not acceptance” approach is one that feels increasingly dated as society acknowledges the injustices of policies like Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Hurley regrettably chose to play a “both sides” approach by including interviews that offered up opinions for how Haywood should present his homosexuality to the world.

Haywood’s husband Steve Hill provides much of the background for their relationship over the years. His scenes are some of the most powerful in the film, emotionally recounting how difficult it was to watch the man he loved celebrate his success from a distance. Hill provides a valuable historical perspective on the closet, immeasurable challenges that America is thankfully moving away from.

What’s sadly missing from Hurley is the idea of resolution for all those years Haywood and Hill spent hiding their relationship. Part of this likely stems from the fact that Haywood didn’t come out publicly all that long ago and still seems fairly uncomfortable talking about his sexuality. There isn’t really any takeaway beyond the sense that Haywood wants to occupy the space between being helpful and a full-on activist. Hurley misses an easy opportunity to shed light on the hardships forced upon LGBTQ athletes, never quite suggesting that something in that culture needs to change.

While it’s easy to understand that Haywood doesn’t want his sexuality to define his legacy, Hurley suffers from a surface level approach to its central narrative. The film would have been better off simply presenting more of a career retrospective, without putting too much weight on Haywood’s coming out to anchor such a large portion of its runtime. Hurley Haywood is an easy man to admire, an individual who achieved great success in a field that still remains hostile to a core part of his existence. The documentary about his life doesn’t really do justice to the man, a film that plays it too safe to present anything meaningful for LGBTQ athletes who might look to Haywood’s story for inspiration.