Sundance Review: The Princess

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

The past year has seen the release of several new works focusing on the life of the late Princess of Wales, but in many ways, it feels weird to label this era a “Diana resurgence.” The public has hardly lost interest in Diana since her tragic death in 1997. Her legacy continues to shape the Royal Family and the public’s engagement with the venerable, archaic institution.

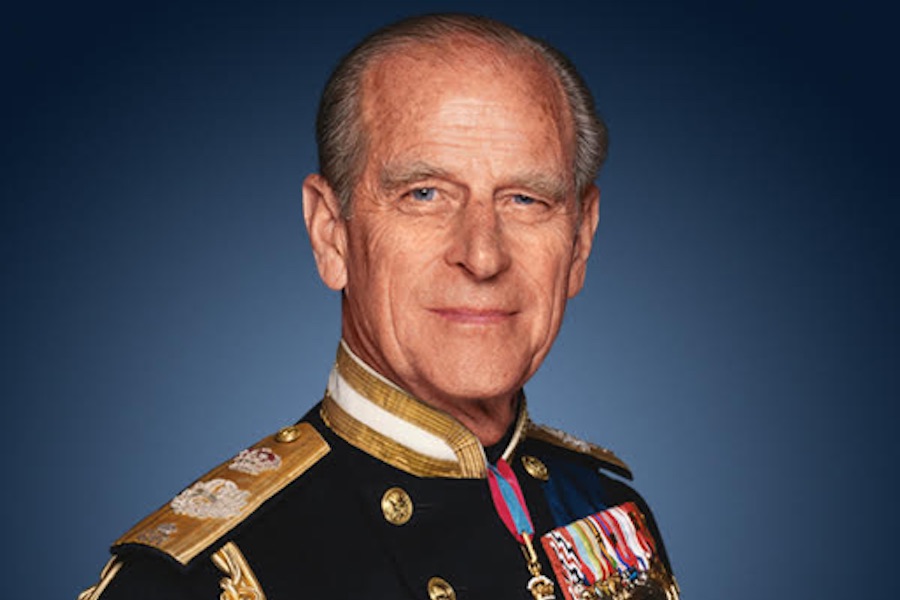

Comprised solely of archival footage and contemporaneous media commentary, the new documentary The Princess takes a look at Diana’s life as it was depicted back then. Director Ed Perkins rarely strays away from the conventional narratives that have developed in the decades since her death. Married at age 19 to the future King of England, a man hopelessly in love with another woman, the Princess of Wales saw her life transform practically overnight into a non-stop media circus that followed her every move, until she was quite literally buried in the ground.

The main overarching narrative of the documentary is Diana’s relationship with the media, though Perkins occasionally switches gears to focus on her doomed marriage to Charles. The lack of modern interviews feels quite refreshing, giving the film space to let its points speak for themselves. There’s no expert testimony about the grueling nature of the paparazzi that could land more powerfully than an extended sequence of the young Diana being unable to even get in a car without being hounded by bizarre intrusions into her personal life.

The Princess possesses a weirdly intimate quality for a narrative focusing on one of the most famous individuals of the era, one that rarely goes more than a single scene without shots featuring hordes of cameras. Aside from Charles, the Queen and the rest of the Royal Family only appear briefly. Perkins repeatedly returns to the tug-of-war between Diana’s modernity and the Firm’s staunch resistance to anything resembling change.

If there are any hidden mysteries about Diana’s life yet to be discovered, Perkins certainly hasn’t found them. The Princess is a gorgeous documentary, albeit one that relies a bit too heavily on its subject’s innate appeal to make its mark in the crowded Diana landscape. The 106-minute runtime flies by, a combination of strong pacing and the breathtakingly obvious appeal of its subject.

Viewers will undoubtedly recognize many of the famous interviews depicted in the documentary, but Perkins does manage to capture the mood of England as the circus unfolded. There is still tremendous power to be found in extended sequences of Diana’s funeral as it was processed by millions across the world, an exceedingly rare global sense of unity. Perkins may not have brought anything new to the table, but his film still packs quite a punch for the countless individuals who still can’t get enough of the Princess of Wales, even after all these years.