Classic Film: Halloween

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews, Pop Culture

Horror movies, particularly those in the slasher genre, exude an aura of indifference with regard to their characters, many of whom exist simply to be killed by the film’s big scary villain. The audience is trained not to get too attached to anyone whose name wasn’t near the beginning of the credits, just as most narratives have plenty of secondary and tertiary characters who don’t play a role in the climax. Gruesome death is largely just a way to pass the time, some warm-up thrills before the big main event.

Many slasher films forget the importance of giving their audiences some morsel of a reason to care about the secondary characters designed to serve as cannon fodder, spending large portions of their runtimes treading water in between murders. Halloween had different intentions. Carpenter’s meticulously crafted film doesn’t waste a single second, the gold standard of the slasher genre with its most effective score.

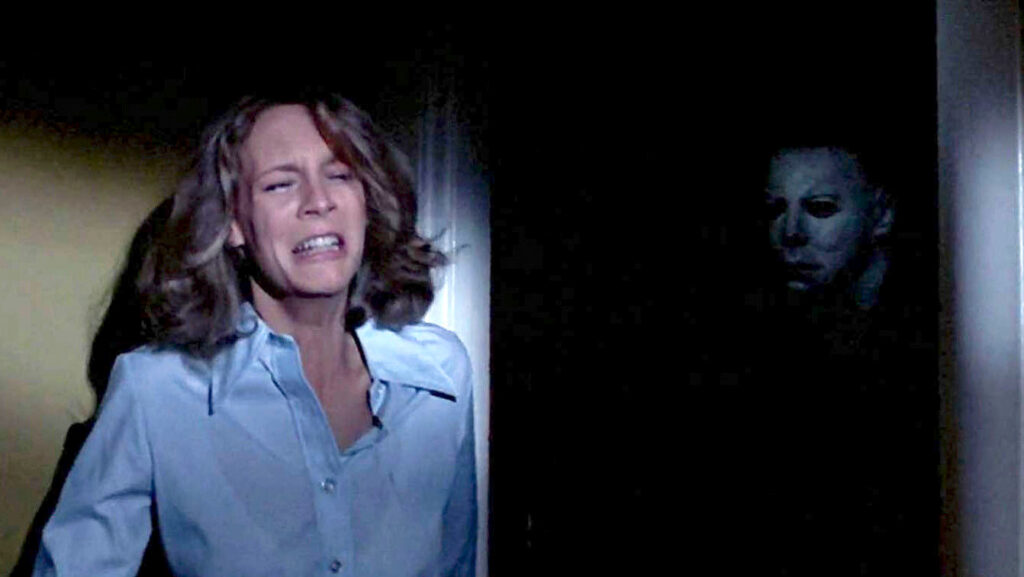

Halloween is an intimate film with few characters. Carpenter doesn’t spend much time exploring the backstories for Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), Dr. Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasance), or Michael Myers (Nick Castle), understanding the inherent relatability of the stakes at hand. It’s not that there’s no time for frivolous backstory, but there’s no real need for it either. The gruesome nature of Myers’ villainy more than speaks for itself.

Carpenter can raise his audience’s heartbeat with a simple piano riff. Night or day, the sound of that melody takes hold of the senses, presenting the idea that anything could happen at any moment. Pleasance and Curtis, the latter making her cinematic debut, are top-notch, but Halloween is the rare film that could’ve coasted solely on the strength of its score.

Michael Myers is the very definition of evil, but Carpenter is careful not to saddle his villain with the bulk of the audience’s contempt. There is much reserved for the institutions that failed to safeguard the world from the boogeyman, including the hospital that failed to contain him and the police who didn’t take him seriously. Myers is not exactly a great example of the cover-up being worse than the crime, but Carpenter manages to spread the blame around.

What’s particularly refreshing about Halloween is the way that Carpenter’s fairly narrow scope feels simultaneously conclusive and open-ended. The bogeyman cannot be killed, not when Myers’ services are required for a dozen sequels. There should be no relief at the end of the narrative, yet Carpenter masterfully eases up on the pressure valve, providing a sense of closure where none should exist. For a genre often defined by low-budget direct-to-video releases, Halloween is a shining example of the power of the form when a master of the craft is behind the wheel.