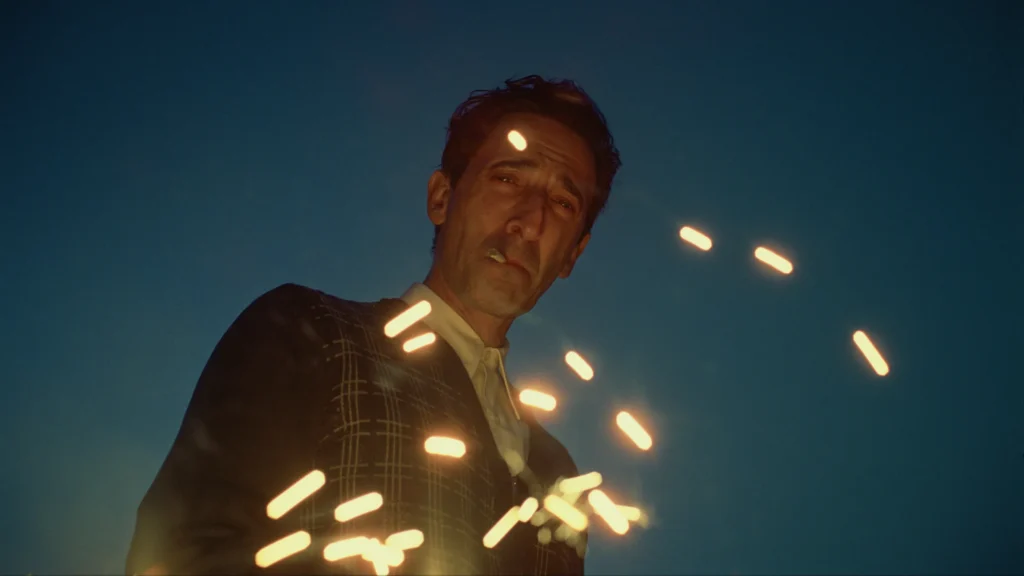

‘The Brutalist’ review: Adrien Brody carries an uneven odyssey

Written by Ian Thomas Malone, Posted in Blog, Movie Reviews

One of the great beauties of the artistic process is the way that the act of creation can help you drown out everything else going wrong with your life. The reconnection with one’s craft can bring the soul back from oblivion, or it can doom an obsessive heart inside a prison of its own making. The film The Brutalist takes its audience on an odyssey through one man’s grief and his efforts to hold on to what’s left of his humanity.

László Tóth (Adrien Brody) is a Hungarian-Jewish architect who arrives to America in 1947 after surviving the Buchenwald concentration camp. Separated from his wife Ezrsébet (Felicity Jones) and niece Zsófia (Raffey Cassidy), László finds work at his cousin’s furniture shop. An expensive commission by a wealthy businessman Harry Lee Van Buren (Joe Alwyn) for his father Harrison (Guy Pearce) gives László a chance to put his Bauhaus education to work in a suitable setting. Harrison’s angry reaction to his son’s surprise renovations causes strife between László and his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), who has already angered László with his assimilation into American culture and conversion to Roman Catholicism.

Harrison seeks out László a few years later, now working menial labor, to make amends and to hire him to design a community center that he intends to construct as a tribute to his late mother. Harrison also pulls strings to have Ezrsébet and Zsófia approved for immigration. László quickly butts heads with Harrison’s team, bristling at any suggested changes and repeatedly clashing with Harry, who resents the Tóth’s presence in his life.

Director Brady Corbet’s most impressive feat is how he makes 215 minutes fly by. The Brutalist is exhausting, but never boring, wasting little of its mammoth runtime. Lol Crawley always keeps things interesting with his fantastic, dreamy cinematography. Even in well-trodden territory, Corbet manages to carve out a fresh perspective on the horrors of that era.

Brody completely loses himself in his lead role. László is a proud man with great depth. Brody captures the essence of a soul that spent too far much time in survival mode, totally immersed by his rare second chance to redefine his own legacy, even at the expense of everything he thought he held dear. Few people who lose everything get a chance to taste the peak of the mountain once again.

The film does fall short in a few crucial aspects. Corbet doesn’t really know what to do with Jones, who doesn’t make an appearance until part two, after a lengthy built-in intermission. Ezrsébet is very charming, befriending everyone in her husband’s extended orbit. There’s tension between the two as a result of Ezrsébet’s decision to hide her health problems from her husband, now confined to a wheelchair from osteoporosis brought on by malnutrition from years of living in famine. The introverted László can wax poetic about the beauty of architecture, lacking that same chemistry with his own wife.

Corbet has such tunnel vision for László that he undersells the rest of the cast. Despite his best efforts, Pearce fails to elevate Harrison into much more than a cartoon villain. We see snippets of his jealousy toward László, who possesses the artistic talent he desperately craves, but his scenes are one-note and repetitive. The depiction of the architectural process leaves a bit to be desired. We see László’s vivid descriptions of his passion for his work, but we rarely see the application of his craft. There’s too much telling and not enough showing.

The shortcomings of Corbet’s storytelling abilities are best apparent through an epilogue tasked with significant heavy lifting for a narrative that had three and a half hours to set up its third act. The Brutalist is a deeply frustrating piece of art. Like its protagonist, you can see the meticulous effort that went into every frame. You can also see the tunnel vision of a mind that may have benefited from additional voices in the room.

Corbet’s vision grapples with Emerson’s timeless saying, it’s not the destination, it’s the journey. A person like László, whose life was filled with unthinkable horrors, might understandably be fixed on the destination as a way to triumph after years of hardship. As for the audience enduring the odyssey that is this film, there’s no question that the journey matters more than the rather underwhelming destination.